The Establishment and Growth of the Port of Charleston

The Port of Charleston, located in South Carolina, played a pivotal role in the economic and strategic development of early America. Established in the late 17th century, it quickly became a vital hub for trade and commerce due to its strategic location on the southeastern coast of the United States. The port’s success was closely tied to the cultivation and export of agricultural products, particularly rice, indigo, and later, cotton.

Geographical Significance

Charleston’s geographic location made it an ideal site for a major port. Situated near the convergence of multiple rivers, the port had direct access to the Atlantic Ocean, facilitating both domestic and international trade. Its proximity to the agricultural heartlands of the Carolinas allowed for the easy transport of goods to international markets, enhancing its role as a major trading center. The natural harbor offered a safe haven for ships against storms, and the depth of the waters around the port enabled the docking of large sea vessels, which were essential for long-distance trade. These geographic features provided Charleston with a natural advantage, setting the stage for its prosperity.

Throughout the colonial period, Charleston’s maritime access proved essential not only to regional commerce but also to the expansion of cultural and economic ties across the Atlantic. The ability to connect with European, African, and Caribbean markets allowed Charleston to grow dynamically.

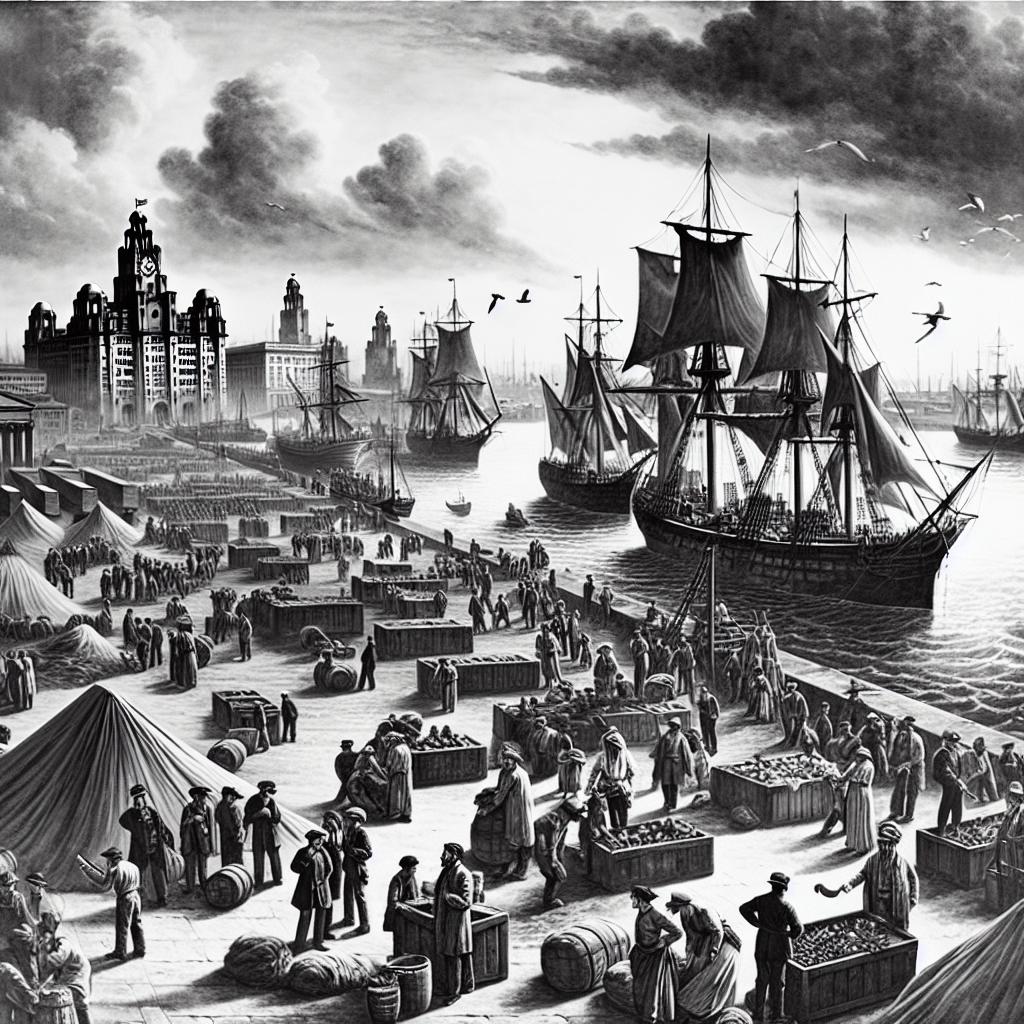

Trade and Commerce in the 18th Century

By the 18th century, the port was bustling with activity as ships from Europe and the Caribbean arrived with manufactured goods, while departing vessels were laden with agricultural exports. Rice and indigo were two of the primary commodities that fueled the port’s economy. These crops were in high demand across Europe, and Charleston quickly became one of the most important ports in the American colonies.

Rice was a particularly lucrative export due to the demand in European markets for this staple food. The profitability of rice agriculture, alongside indigo used for textile dyeing, contributed to Charleston becoming the wealthiest city in the American South by the mid-18th century. The development of rice as a major export was tied to the extensive networks of plantation agriculture that dominated the Southern landscape.

The 18th-century expansion of Charleston’s trade routes allowed the city to become a nexus of mercantile activity, where merchants and traders facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices. This period marked a high point in the port’s economic influence, making it a key player in the trade networks of the Atlantic world.

Role in the Slave Trade

Unfortunately, Charleston’s growth was also intertwined with the transatlantic slave trade. The port served as a primary point of entry for enslaved Africans brought to North America. The labor of enslaved people played a critical role in the cultivation of the crops that were exported through the port, highlighting a tragic aspect of its history. The reliance on enslaved labor for crop production was systemic, and the port became one of the most significant centers for the trade and auctioning of enslaved people in the United States.

The human cost of this labor was immense, and the wealth generated through the port’s activities was inextricably linked to the exploitative practices of slavery. This aspect of Charleston’s history serves as a poignant reminder of the broader socio-economic structures that shaped the early American economy.

The Port of Charleston in the Revolutionary Era

During the American Revolutionary War, Charleston’s strategic importance increased, both as a major supply base and as a British military target. The city was captured by British forces in 1780, demonstrating its significance in the conflict. The port’s capture by British troops represented a major strategic victory, providing them with a base from which to launch further operations in the Southern colonies.

The wartime experiences of Charleston underscored the city’s critical logistical role. Supplies and reinforcements flowed through its docks, making it a hub of military activity. Despite the turmoil of the Revolutionary War, the port’s essential status remained unchanged, and it emerged from the conflict retaining its prominence.

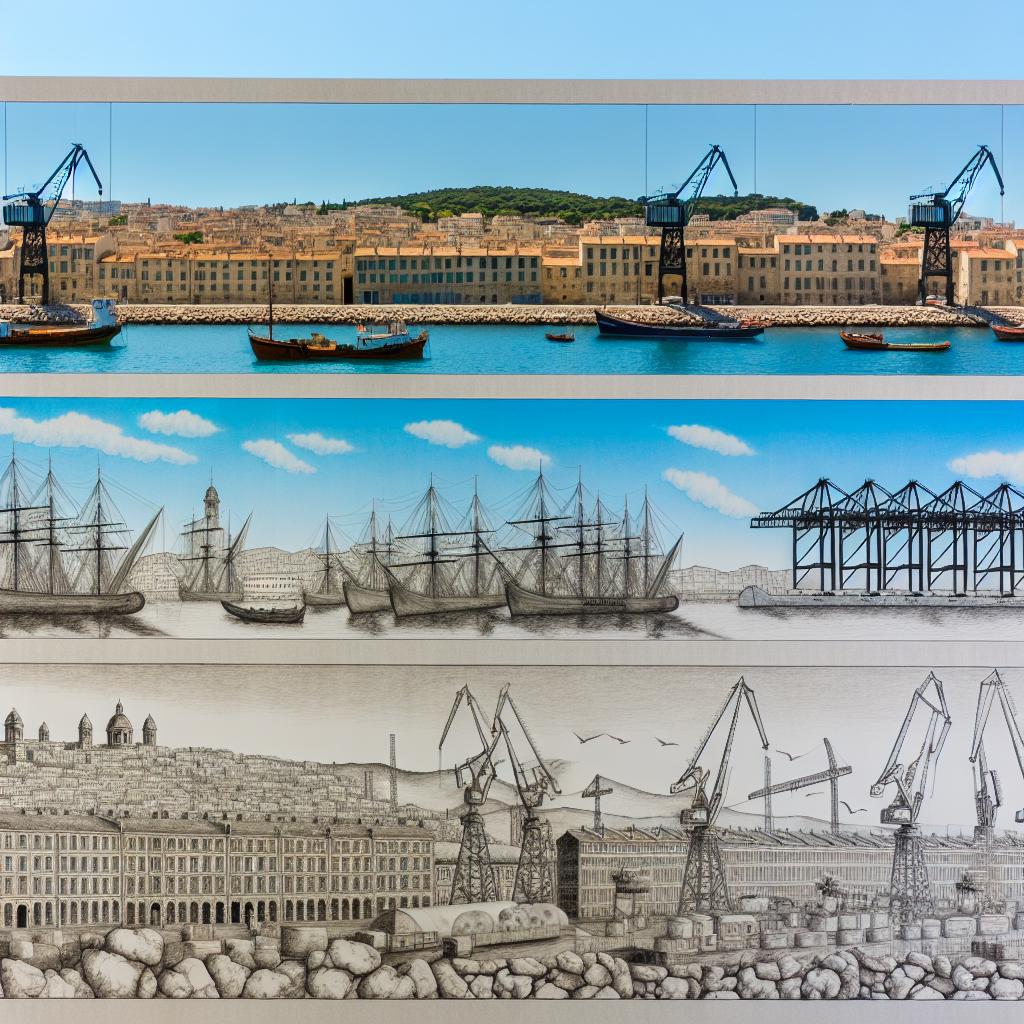

Post-Revolution Developments

After the American Revolution, the port continued to prosper, particularly with the rise of cotton as a dominant cash crop. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 significantly boosted production, solidifying Charleston’s role as a major export center well into the 19th century. The cotton gin allowed for quicker processing of cotton fibers, which in turn increased the volume of cotton that could be marketed and exported.

Throughout the 19th century, Charleston maintained its status as a key economic center in the South. The port’s infrastructure was expanded to accommodate the growing trade, and new trade routes developed in response to shifting economic demands. Innovations in shipping and transportation, including the advent of steamships and railroads, further integrated Charleston into national and international trade networks.

In conclusion, the Port of Charleston was critical to early American economic development. Its location fostered a thriving trade economy while also tying it to broader global networks. Despite its significant contributions to economic growth, the port’s history is a reminder of the complexities and contradictions of early American society, particularly concerning the reliance on enslaved labor. Its legacy is multifaceted, reflecting both the entrepreneurial spirit that drove its success and the enduring impact of the oppressive systems it supported. The evolution of the Port of Charleston provides insight into the broader narrative of American economic and social history, showcasing both progress and the moral challenges of the time.